Last week I finished teaching the first iteration of my webinar course on geomancy, which was graciously hosted the magnificent chaps at Wolf & Goat. One of the things I compiled for students taking this course was a list of links to download scans of early modern geomantic texts. Considering these links are all available on my tumblr, Grimoires On Tape, it made sense to turn this list into a full survey blogpost for those interested in diving into the geomancies of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Anglosphere. This piece can also be considered a sister-post to my brief survey of modern secondary sources on geomancy, An Earthly Garden.

And so I present links and summaries to my favourite early modern geomancy texts.

Of the many sixteenth-century French texts of geomancy, The Geomancie of Mr Christopher Cattan is one of the few to be translated into English, coming onto the English vernacular magical scene in 1591. Stephen Skinner describes it as ‘immediately becoming a best-seller which necessitated its reprinting in 1608’, and claims there were numerous contemporary manuscript copies based on this work.

Cattan describes geomancy as not only a ‘daughter of Astrology’, but ‘a part of Natural Magicke’. His correspondences of zodiacal signs to figures are a little idiosyncratic, but the teachings of the techniques are relatively solid, and the treatments of the geomantic figures in their various houses is straightforward.

A word of warning: every early modern edition I have found of this text is printed in horrendous gothic blackletter typeface, and can give headaches from exposure over long periods of time. Unfortunate, for I'm sure this text would be more widely used if simply transcribed into a less nightmarish font.

(Txt version: https://1drv.ms/t/s!AqUWUXQe5AkngWkdqjT4LAQjfA1Y)

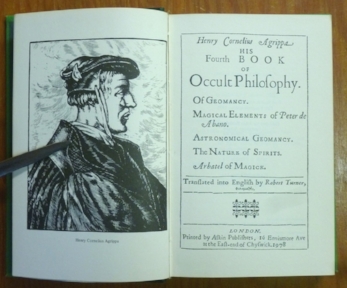

The Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy, to which the attributed authorship of Agrippa himself has been questioned, is a collection of magical treatises. In contrast with the survey-like quality of the treatment of geomancy in the Three Books of Occult Philosophy, the Fourth Book has a decided emphasis upon the practicalities of how to actually carry out operations of ritual magic - and especially how to geomance. Alongside the Heptameron (a system of circle magic incorporating petitioning and charging angels to carry out one’s will) is the text On Geomancie, which consists of instruction in how to generate figures, create a chart, assign figures to houses and interpret interrelations.

While eventually not as detailed as Cattan or other dedicated manuals of geomantic divination, it is probably the clearest take on beginning to learn geomancy from early modern texts. The author lays out a number of different elemental configurations of the sixteen figures, and these alone are worth meditating upon. The various other essays and grimoires that make up the Fourth Book are also important for understanding the context in which many seventeenth-century geomancers first engaged with their craft.

Heydon's Theomagia is a text that not only undoubtedly influenced the later geomantic practices of the nineteenth century, but that presents a somewhat more explicitly magical contemporary approach to seventeenth-century geomancy. John Heydon’s Theomagia or The Temple of Wisdom (published in 1664) is a handbook-cum-extended-ramble that teaches ‘how to project a figure the Rosie Crucian way’. This whole ‘way’ conceives of geomancy in a somewhat unusual light: specifically, in terms of spirits and angels. The astrological symbol components of this system are utilised by the magician as reified through a committed angelological animism – Heydon does not talk about the planet Mars or the sign of Aries, he speaks of the Ruler Bartzabel and the Genius or Idea of Malchidael.

This spirit-heavy approach to geomancy even seems to have had implications of possession and trance states. Heydon states that, when drawing the figure, if performed properly, ‘the hand of the projector or worker [is] to be most powerfully moved and directed by the Idea’s or Genii when they Ascend and Descend...’

Such fascinating perspectives and practices I feel more than make up for Heydon's frequently garrulous tangents, such as quoting several whole chapters of Agrippa's Three Books verbatim. It is not an easy book to read, but if you can get past the hundred or so pages of self-congratulatory introduction and his frequent aristocratic waffle, I think this tome might include some of the most "magical" approaches to European geomancy we have at present.

The final set of primary sources I would like to direct you to is the Casebooks Project, a digitised and searchable archive of early modern astrological and geomantic case files. These are the patient and client records of Doctors Simon Forman and Richard Napier, detailing their divinatory consultations for the period between July 1597 and August 1606. They offer glimpses into the practices of early modern diviners and the very human concerns and hopes of their clients.